Quaker responses to spoken ministry in meeting for worship typically fall somewhere between amused tolerance and exasperation. It is very common to hear complaints about ‘daffodil’ or ‘Radio 4’ ministry. For some, any spoken ministry is an unwelcome interruption of their own thoughts. People rarely describe ministry as important for nourishing their spiritual life.

This is a problem, because spoken ministry is a crucial part of Quaker worship. If the ministry that usually happens in meetings is so often unhelpful, superficial or predictable, we have lost a core aspect of our most important spiritual practice.

Earlier generations of Quakers took the call to minister very seriously. It was a response to a divine leading, and not something to be lightly undertaken or neglected. John Woolman wrote about the first time he spoke in meeting:

“One day, being under a strong exercise of spirit, I stood up and said some words in a meeting; but not keeping close to the Divine opening, I said more than was required of me. Being soon sensible of my error, I was afflicted in mind some weeks, without any light or comfort, even to the degree that I could not take any satisfaction in anything… About six weeks after this, feeling the spring of Divine love opened, and a concern to speak, I said a few words in a meeting, in which I found peace.”

(Journal of John Woolman, 1774)

A calling to regular spoken ministry entailed the obligation to develop their spiritual understanding and discernment, so they could minister more faithfully. It also required the support of the meeting, particularly from elders. Eldering was understood as an active and supportive relationship to nurture the gift of ministry, not just disciplining inappropriate speech.

Today it seems to be rare for meetings to offer any positive guidance and support for spoken ministry. Many elders lack the confidence either to discourage unhelpful ministry or to nurture people’s spiritual gifts. This has led to a situation in most Quaker meetings where spoken ministry is almost unknown, or where it is most regularly offered by those who have done the least reflection and discernment.

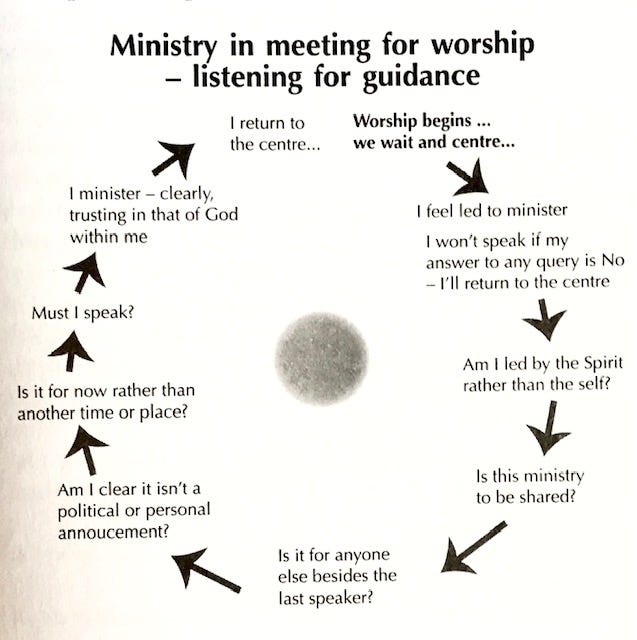

Quakers are sometimes offered guidance in the form of a diagram for testing a leading to minister. One of the best versions of this is in ‘With a Tender Hand’ (Zelie Gross, 2015), reproduced with permission below:

It is noticeable that all versions of this diagram are clearly intended to inhibit unhelpful ministry, rather than encouraging those who are hesitant. If this guidance were widely followed, there would presumably be much less commentary on the news or summarising of Radio 4 programmes. But the question ‘must I speak?’ would also discourage anyone from ministering unless they were in the grip of some extraordinary compulsion.

Good spoken ministry is not something that can be reduced to a formula. Like many other kinds of human activity, it is developed by practice and reflection. It can be improved by cultivating our own spiritual understanding and sensitivity. With practice, we can learn to distinguish between how it feels either to minister faithfully, or to ‘outrun the Guide’, by saying more than is needed.

Good spoken ministry is both a sacred obligation and a practice to be cultivated over time. It touches the heart and opens the mind to new insights and possibilities. It is essential for newcomers to discover the potential of Quaker spirituality and for meetings to thrive.

In my own meeting the quality of spoken ministry has improved dramatically over the last couple of years. Sheffield Central is a large meeting and has always had regular ministry, often of the sort that is tolerated rather than welcomed. But now we more often hear ministry that comes from a deeper place of vulnerability, that expresses people’s longing for hope and connection, and their experiences of spiritual encounter, comfort and challenge.

When people are brave enough to go deeper in their ministry, it encourages others to take the risk of being more open and authentic. It also creates an atmosphere of energised expectancy. The silence feels charged with potential and resonant with spiritual openness and intimacy.

People in our meeting now look forward to worship with a sense of expectation and excitement. When I’ve been away on some Sundays recently, friends who have been members for many years have told me feelingly about the extraordinary meetings I’ve missed.

Not coincidentally, our meeting has also grown rapidly, as newcomers of all ages keep coming back and bring their friends, because they have experienced something that speaks to that of God in them.

None of us are perfect judges of spoken ministry. There will inevitably be things in our own temperament that obscure the value of a piece of ministry which is helpful for others. We need to be gentle with ourselves and our Friends’ inevitable mistakes and imperfections. Part of learning to improve is trying and falling short. But this is not the same as saying there is no standard of faithfulness to aim at. Spoken ministry doesn’t need to be perfect, it just needs to have life.

Quakers so often say they are not nourished by their meeting, that they don’t know each other deeply, they have no idea what people in their meeting believe or experience. This is what spoken ministry is for. It is ministering to each other.

It is certainly true that there are no rules for (good) ministry. There are, however, some useful guidelines: it should be brief, not overly developed or structured, not intellectualised; in essence, the best ministry is like poetry delivered with gentle simplicity.

I tend to get uneasy when Friends talk about 'good' ministry as it is such a subjective thing. I recognise when ministry speaks to me and try to be patient when it doesn't, particularly when after meeting Friends tell me how helpful the 'unhelpful' ministry was for them. Ministry has changed over time and will, I hope, continue to evolve. It is almost unheard of now for a minister like Ann Wilson to point a finger in admonition of an individual (Samuel Bownas) or for anyone to, as Anna Braithwaite did in the 19th century, speak 'for an hour, fluently elucidating many gospel truths'. But if we are faithful to our leadings to speak when we are moved, and not to speak when the time is not right, then who knows what ministry may emerge?